Modern football through the lens of René Girard

I occasionally write about interesting ideas I learned elsewhere, import them into football, and try to figure out how to combine them. If you would like to receive the next edition, subscribe below:

The proposed Super League was the tip of the iceberg – a closed league of the wealthiest clubs in the world patterned after the American franchise model. It escalated a development that has been going in for years. Who does football belong to?

“Football: created by the poor, stolen by the rich.” has become a quote that summarizes the feeling among many supporters. There’s a strong belief that some outsiders stole their beloved sport, using it as a lever to become richer. In that sense, the Super League felt like another attempt to push them out – to destroy and monetize their childhood memories.

Nowhere was the anger about the new league greater than in the northwest of England, in the city of Manchester. A city that was the heart of the industrial revolution, bombed during World War II. A city of the working-class people, who founded a football club that united them, that gave them hope and should become one of the most famous clubs in the world.

The Super League ultimately collapsed within no time; it became a debacle for everyone involved. At the same time, it was grist to the mill for every critic of modern football. Right now, there seems to be peace – at least temporarily.

This whole development poses questions. Lots of questions. How did we get to this point? How did we get to the point of a two-tier society in football – a game that is supposed to unite people no matter their background – where some people no longer feel wanted? Where is the end to this conflict? Is there an end to this conflict?

Wright Thompson

Someone who might have also asked himself these questions is Wright Thompson. In his piece “Super League rage, Ronaldo mania and the fight for the soul of Manchester United”, Thompson explains in great detail the history of Manchester United – from the Industrial Revolution to the birth of the modern Premier League – and highlights the meaning for the people of Manchester.

As one of the most important parts of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, Manchester was a welcome target for enemies in the post-war period from 1945. Many people lost everything. United’s team at that time – the so-called Busby Babes led by manager Matt Busby with an average age of 22 – gave many people a sense of purpose, a feeling of happiness after the terrible experiences of the war.

On February 6 in 1958, this feeling of happiness was shattered when the club’s greatest tragedy occurred: the plane crash in Munich. Twenty-three people died, eight of them United players. It was a disaster for a group of people who looked up to this team in the hope of better times to come. These players were one of them.

After a period of despair, mourning, and numerous funerals, a new beginning followed. A new beginning that would make Manchester United the most successful club in England. A new beginning that brought joy back to the people. The plane crash made people suffer but it also welded them together. United became like a religion – a place where all sorrows are forgotten for some time. The meaning to the people can hardly be overstated and Thompson does a great job of highlighting that.

Then came globalization. And with globalization came more capital, more labor, and an increasingly interconnected world. Things started to change.

On ESPN Daily, Thompson rephrased John F. Kennedy’s famous quote that “A rising tide lifts all boats” to “A rising tide lifts many, many boats”. While the original quote is to say that a growing economy benefits all participants, Thompson restricts this thesis. Globalization may benefit most people, but not all – at least not to the same extent.

In this case, it’s the Mancunians – the people of Manchester. Mancunians who can’t buy tickets anymore, who have to watch how wealthy owners monetize the memories and the history of their club. And it’s not only that. It’s also that their team is not successful anymore. While United has been struggling for years, other teams like Manchester City have benefitted from globalization through their nation-state owners, having long surpassed the Red Devils.

René Girard

When reading Thompson’s piece, I couldn’t stop but think about René Girard. Girard is a French historian, literary critic, and philosopher. He, too, thought about the role of globalization in our modern world and warned against it: "When the whole world is globalized, you're going to be able to set fire to the whole thing with a single match."

Girard, however, did a lot more than that. He spent his life trying to understand human nature and its desires as well as the role of scapegoating and violence in our society. At the core of Girard’s worldview is his Mimetic Theory. Mimetic Theory is controversial to some as it overturns some widespread assumptions of our society.

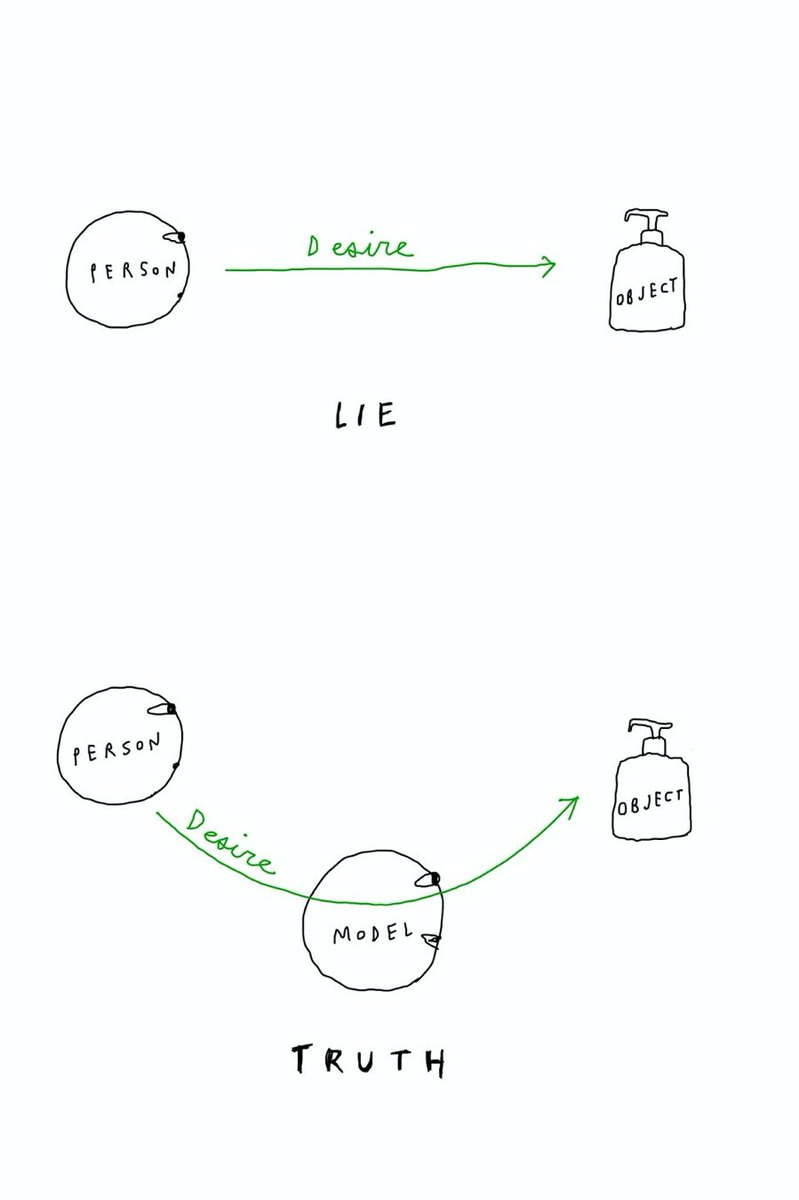

One of the core components of Girard’s theory is his notion of humans as imitators. We are, after all, social creatures. Girard argues that we don’t develop our own desires but want what others seem to want. Once our basic desires – such as food, water, sleep, and shelter – are met, we adopt other people’s desires. It’s why advertising works and why stock markets rise and fall.

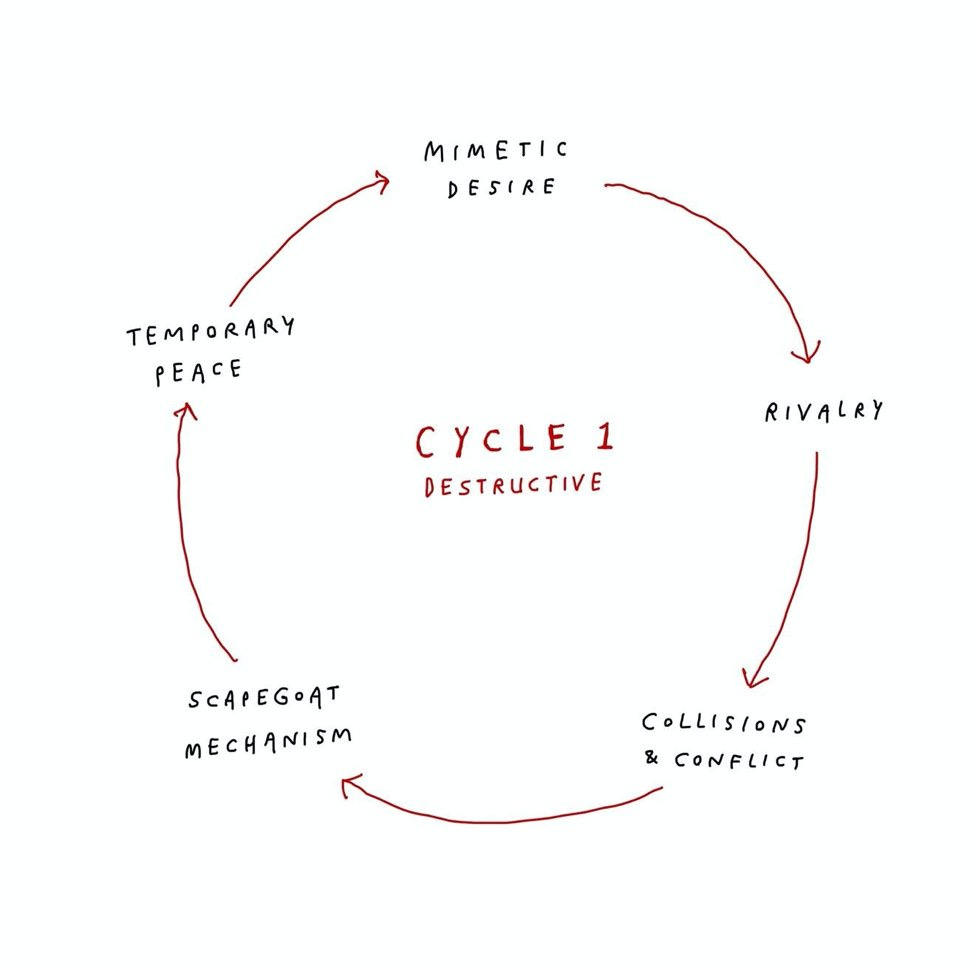

Girard’s theory about mimetic desires also provides an explanation for human conflict. We don’t fight about reading a book because there’s enough for all. Problems arise when the object is scarce or cannot be shared. As we want the same thing, we start fighting over it. This leads to Girard’s claim that mimetic desire leads to mimetic rivalry and conflict.

Eventually, this conflict must be solved through a scapegoat – one individual or group that is made responsible for the social contagion. The underlying belief is that the scapegoats are the source of all problems. Their elimination will bring back peace to the community.

This was only a glimpse into Girard’s theory. Throughout this article, we will delve deeper into it and explain how it maps to the development of modern football. Girard’s worldview does not offer the universal explanation of how football developed. On the contrary, there’s plenty of room for disagreement. But it can offer a fresh perspective and another layer to Wright Thompson’s explanation. Three blocks will guide us towards a better understanding:

Mimetic Desire

Mimetic Rivalry

Scapegoating Mechanism

___

Disclaimer 1: All quotes are from Wright Thompson’s piece on Manchester United and his podcast appearance on ESPN Daily unless otherwise stated.

Disclaimer 2: Girard’s worldview is complex and only a small part is covered here. The contents of this piece are based on books and articles about Girard, some of which I will reference at the end. I hope some of it is interesting. Some of it might be wrong.

Disclaimer 3: I don’t necessarily agree with all of Girard’s points, but I admire his reasoning. I believe his thoughts provide a different and unique perspective on many things, not only football. Something you’ll often hear from people who read about Girard is that you will start to see mimetic theory everywhere. I couldn’t agree more.

___

Part 1: Mimetic Desire

Humans are imitators

We human beings like to believe that we are somewhat unique, autonomous creatures. We like to believe that we develop our own desires, that we don’t care much about cultural and societal norms. We like to believe that we constantly choose our desires—that they’re “just right for us”. We like to believe that we follow our hearts. In Girard’s view, this is nothing but a romantic illusion.

One of Girard’s fundamental, if not the fundamental, warning is that humans are imitators: we learn by watching and copying others. We find people we admire. We start to imitate their language, their habits, and, most worryingly, we start to imitate their desires. We want what others seem to want in order to become like them.

The best example of imitators is kids. Kids are learning machines. Kids know nothing when they come into the world. They have to acquire a language, learn how to walk, learn how to behave and so much more. How do they do that? Kids do that by paying attention to other people, by imitating you. They want what you have and want to do what you’re doing. They want to be like you.

Girard calls these people from whom we learn “mediators” or “models”. These models are an essential component of his mimetic theory. We develop our desires through them.

Globalization and the internet

While imitation has been ever-present at all stages of history, globalization and the internet made it easier than ever. It decreased the distance between humans from all over the world. It connected us. It made us peers. We could no longer just learn from people in our neighborhood but from people from all over the world.

Put differently, globalization and the internet have increased our radius of envy. Suddenly, it was not only the people of Manchester who were exposed to the greatness of United. It was everyone with a TV or internet connection. Everyone could see them play. Everyone could get a glimpse of what makes them special.

And people loved what they saw. They loved what they say on the pitch but particularly outside of it: the atmosphere, the feeling of being a part of a club like Manchester United. They admired the people in the stadium – their spirit, their joy. They might have not understood their roots, but they developed a desire to become members of this passionate community that is united in its support for one particular football club. In Girard’s words, the people from Manchester became models for people from all over the world.

“If you have ever been to a game at Old Trafford or seen one on TV: all of those super-complicated fierce ideas about this tribe are somehow communicated by the experience of watching them. People at home understood it. Everybody from outside of Manchester understood what that name on your shirt meant. And people wanted it.”

Part of what makes Manchester United so special and attractive for others – especially rich people – is that the club is such a societal touchstone. Toddlers, teenagers, workers, grandparents – people argue over it every day at work, school, or at the dinner table. These wealthy owners could have literally anything, but, paradoxically, they want what the working-class people want because they can tell how much they want it and how much they care. In Girard’s view, the more other people want it, the more attractive the object becomes for us, too.

All that said – and this is an important part of Girard’s theory – people didn’t develop this desire for the value of the object or the value of the experience itself. It’s not about buying a scarf or watching a match live in the stadium. It’s about being. In Girard’s words, it’s about “to be what the other becomes when he possesses that object.” It’s what the advertising industry does all the time: “Be like Mike”. It’s not about drinking Gatorade because of that object. It’s about being like Michael Jordan when you possess that object. Possessing an object in our case can mean different things to different people. It can mean owning the club, it can mean possessing a membership card, it can mean possessing a jersey, etc.

Search for a community

Another factor at play in this development is somewhat paradoxical. While globalization connected us, it alienated us at the same time. It’s the contradiction of social media: the fact that we can see and have everything in an instant makes us feel lonelier than ever. It allows us to follow other people's lives at every turn, to constantly compare ourselves with them – often at the expense of our own personal relationships and wellbeing. It creates pressure to become like other people we admire.

The willingness to belong to something, the willingness to belong to a community, however, is deeply rooted in all of us. Maslow ranks love and belongingness as the third most important in his hierarchy of needs and studies emphasize their importance. We all desire to be part of a group – even more so when we are not.

Football, the love for a club, can provide that. When globalization accelerated, many clubs could look back on a decade-long history – marked by successes and failures, celebrations and tears. These experiences connect people, they form bonds and make for a passionate community. A community everyone could see now and have access to.

Part 2: Mimetic Rivalry

When mimetic desire turns into mimetic rivalry

So far none of this seems suspicious. We have an increasing number of people admiring and supporting the same club which is actually … a good thing, no? Girard agrees with that view. As long as desire is directed at an object that can be shared – learning a language, reading a book, drinking Gatorade – mimetic desire poses no problems.

This changes when the object is scarce and can no longer be shared: objects of sexual desire or social positions. These are the situations that Girard warns against. These are the situations where models and their admirers can eventually become rivals due to their mutual desire.

At first glance, you would put, football, the love for a club, in the first bucket. It is something that can be shared. It’s not a zero-sum game but brings people together in harmony. Girard, however, might have disagreed with this statement as he disagreed with the statement that China’s economic growth would be beneficial for its relationship with the US.

The growth of China has obvious benefits for everyone involved. The West receives cheaper goods while the Chinese improve their wealth. Girard, however, saw the caveat of this growth and the alleged advantages early on: the gap between China and the US diminishes. It threatens power. It threatens social standing.

Put another way, status and social standing are zero-sum games. Mimetic conflict emerges when two people desire the same, scarce resource. Is China the most powerful country in the world or is it the US? Is Manchester United the club of the working class who founded the club, who buried players after the plane crash in Munich, who rebuild it, for whom football is really more than a game? Or is Manchester United this global giant, the club of the affluent that many ordinary people don’t have access to because they can barely afford it?

“People feel like a group of outsiders, trying to make money have monetized their memories of their mothers crying and listening to the radio, hearing news of a plane crash in Munich. And that they are now being asked to pay more for what used to be their own memories. Many of them are finding that they don’t have the money for it and those that do have the money for it don’t have the stomach for it.” (...) “Anything that diminishes the local in favor of wealthy internationals is the perceived enemy of the British working class, whether that is the European Union or a football league”

We don’t fight because we’re different; we fight because we’re the same

There are multiple ways how to frame this conflict. Rich against poor. Modernity against tradition. Capitalists against working-class. Choose the one you like. What they all have in common is that they are opposites. It seems reasonable that these opposites are the reason for conflicts. Conventional knowledge says that we fight because we’re different. We fight because we have different goals, different values, different incentives.

Girard, however, turns this around. He views these opposite positions as false differences – slogans by both sides to justify their aggression. In his theory, the primary causes of conflicts are similarities: we don’t fight because we’re different; we fight because we’re the same.

This may well be one of the hardest parts to grasp of Girard’s worldview because it’s so counterintuitive. It’s not that there are no important differences between the groups. There are lots of differences. Girard’s point is that these differences are not the real cause of conflict and that we should focus on the vast similarities they share:

Searching for a community

Being football fans

Escaping from everyday struggles

Competitiveness

Passion (each within their boundaries)

Dislike for other teams

Love for the players etc.

Internal and external mediators

The fact that mimetic desire can turn into mimetic conflict in the first place relates to the distance between the participants. Girard distinguishes between internal mediators and external mediators. External mediators are God-like figures, people who are very different than you: a king, a president, or a legendary football player. You admire them, but there’s absolutely no basis to compare yourself with them, hence no risk of envy and conflict. According to Girard, this is what makes them good models.

Internal mediators are dangerous. They are your peers – the reason for conflict and rivalry. You want to be like them and naturally compare yourself to them. It starts with admiring other people for who they are. They become our models; we want what they want, and we try to copy them in order to become like them. At some point, however, the relationship starts to transform. People we recently admired become rivals because we converge and compete for the same thing.

This distinction brings us back to the influence of globalization and the internet. Globalization and the internet made us all peers because they minimized the distances and increased our radius of envy. It was no longer just the people of Manchester who could be part of this special football club but people from all around the world. The more negligible this distance becomes, the more probable it is that mimesis will end in rivalry and conflict.

In addition, from a different perspective and somewhat paradoxically, the radius of envy for the working class of Manchester has increased, too. These people can now see how Barcelona, Real Madrid, or Bayern Munich are successful and they want that, too. In that sense, the chaotic situation around Manchester United acts like a fire accelerator for the entire conflict. Many clubs have foreign, wealthy owners and many clubs have similar issues that traditional United supporters have. But most of these clubs are successful – or at least more successful than they were before. With United, it’s the other way around. Their club used to be the best but right now it is just no longer good and that makes people angry.

Part 3: Scapegoating mechanism

The question that mimetic rivalry poses is clear: How does this get resolved? In a premodern society, Girard describes mimetic rivalry as the most dangerous threat to communities. The rivalry magnifies over time and it’s difficult to stop. With no formal justice system in place, this would lead to endless cycles of violence and the erosion of social and cultural structures. Back in the day, there was another way to end this conflict: find a scapegoat.

The idea behind a scapegoat is that two competing groups channel all the violence and blame into one specific person who is made responsible for the entire conflict. This person is most likely not even guilty. He is sacrificed for the greater good to create the impression that all problems are resolved, and we can live in peace again. It’s important that the scapegoat is neutral so that both sides are satisfied. If the scapegoat belongs to one group or the other, the respective group will feel disadvantaged, demanding a response and thereby creating a vicious cycle.

In theory, the fundamental principles of this scapegoating mechanism are still present in modern societies. Wherever there are problems, we look for a scapegoat to blame and try to redeem ourselves by doing so.

The cancel culture is a modern phenomenon of that. In Zero to One, Peter Thiel writes: “The famous and infamous have always served as vessels for public sentiment: they’re praised amid prosperity and blamed for misfortune. (…) Who makes an effective scapegoat? Like founders, scapegoats are extreme and contradictory figures.”

In sports, scapegoating happens all the time. Just think of the last time your favorite team fired their head coach. After a bad run of results, firing the head coach is often the easiest way to blame someone for all problems. We typically hear phrases such as, "Unfortunately, he could no longer reach the team." or "We have lost faith in his tactical ideas", followed by optimistic outlooks on the future: “We hope for a new impulse for the team”.

The same also happens on a player level. Think of United’s Harry Maguire who has been widely criticized for his performances this season. Interestingly, this singling-out mechanism just exemplifies our mimetically-driven behavior. People imitate each other in their desires, but they also imitate each other in their dislikes. Therefore, when you have public criticism like on social media, there will be more and more people who jump on the train after the first stone is thrown. It becomes easier and easier for each one who jumps on the train as the group gets bigger.

The Super League drama is another example of scapegoating. When the clubs communicated the benefits and necessity of the new league in an impressive and hard-to-refute manner, they blamed UEFA, arguing that they had no other choice than to break away in order to save the entire football industry. The UEFA is not popular among traditional fans either, so it would have been an appropriate scapegoat that both sides could agree on.

However, the crux is that scapegoating only works as long as it happens subconsciously, and people don’t realize that they are involved in it. This is clearly what people realized in the case of the Super League. Nobody believed that these wealthy owners wanted to break away from UEFA to save the football industry. Similarly, when your club changes its head coach for the second or third time in a season, people start to realize that the coach might not be the actual cause of all the problems.

The main issue with scapegoating is that while we think we’re getting rid of the problem, it doesn’t resolve the actual problem. In that sense, the scapegoat mechanism distracts us. It keeps our eyes from seeing – or trying to figure out – what is actually going on. It is only a short-lived solution, a temporary suppression of the cause of the conflict. Sooner or later, it will work its way back up.

Where do we go from here?

If scapegoating doesn’t work permanently, what does this leave us with? Are we forever trapped in the flywheel of seeking a scapegoat to establish short-term peace, crumbling again after a short time?

We might be. Girard argues that imitation is inevitable. We cannot resist that contagion and that will never change. He refers to scapegoating as a rite, i.e., a community’s controlled repetition of this mechanism. It is not a one-time time thing but continuously used to restore peace and unity.

The only way to escape this conflict in Girard’s view is to focus our attention on hierarchies and find the right people to imitate. Girard talks a lot about religion which is the ultimate source of hierarchy. It goes back to his concept of external mediators. Hierarchies create a distance between two individuals that, in turn, avoids jealousy and resentment. We are a lot more jealous of someone close to us than we are of a king or some divine personality.

Of course, Girard thinks of very different things when he talks about religion and God, but the love for a club is in many ways like a religion. Think about it: rituals before, during, and after the game; group singing; deep emotional involvement; the use of symbols to show that you are part of a certain group. These are all religious aspects. Every club has legendary players; heroic figures, shaped by immortal memories, admired by everyone at the club. Focusing on these religious beliefs and external mediators can serve as a defense against jealousy and mimetic rivalry.

This is, indeed, what parts of United’s traditional fanbase did. They did escape the conflict. They took their religious beliefs and moved on with a new chapter of United, supporting a lower league club of Manchester. At the center of their mythology? The legendary Nobby Stiles.

"This is a club that appeals to Manchester United supporters," Seddon says. "But we are Manchester United fans who don't feel like we have a place at Old Trafford anymore. For us it's not a new team. It's a continuation of Manchester United -- but the good bits we like from Manchester United."

Most people, however, don’t give up on their beloved club. They find themselves on the borderline between competing and cooperating with the upper class: competing for their relative status as part of Manchester United but also cooperating by buying tickets or merchandise. While Mancunians continue to stand up against the rich, they may still find some sort of peace through the religious belief in their club and the admiration of legends like Nobby Stiles that gives them hope. Hope that all of this may change one day.

“The fight between Mancunian supporters and the forces of globalization pushing them out and replacing them with rootless strangers hasn't been decided. It is happening in real time. The most important fights aren't won by great generals on decisive days, like in the movies, but slowly over time, a few grains of sand at a time until a world is washed away. Like so many places, Manchester is engaged in a mostly hidden war over what it means to be from here.”

Additional Reading:

This long-form article is probably the best introduction by Alex Danco

This talk by René Girard is a great explanation by himself

Wanting by Luke Burgis is a very approachable book into Girard’s theory

This book goes deep into the origin of Girard’s ideas and where we can find them in historical texts